The recent race-hatred murders in Charleston, South Carolina and the heightened debates about reforms to mass incarceration and criminal justice, highlight the urgency of examining race as a critical factor shaping contemporary American life. It is inescapable – whether we think we are beyond it, whether we focus our attention on it, or wish that we have moved beyond the evils of racism. Higher education has a special responsibility to engage in a critical discourse on race. Colleges and universities are animated by values of personal and professional development, truth, knowledge, and fundamental respect for humanity. They aspire to be model communities. If we cannot think and talk frankly about race within a college, where can we?

One of the challenges in engaging in this dialogue is separating personal experience, which is often undeniable, with what happens more broadly. Personal history may teach something. However, it may not be universal or actionable. Further complicating the discussion, who gets to speak from a position of authority? If we acknowledge that difficulty of dialogue around race, listening becomes all the more important. I am a privileged white male. Listening is all the more valuable and important.

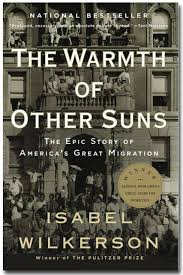

Trained in history and having spent decades in higher education, I often rely on scholarship to help sharpen understanding and increase awareness. With that in mind, I recommend two books: Isabel Wilkerson‘s Warmth of Other Suns and Michelle Alexander‘s The New Jim Crow. Both are skillfully argued and written. Informative and compelling, they are worth your time and consideration. Read together, with an open mind, they offer a mutually reinforcing perspective on how racism and the politics and power of race plays out in America.

Wilkerson’s book is about the great migration of African Americans from the South to other parts of America. She mixes economics and statistics with personal narratives and quotes, focusing on the stories of three individuals and their journeys. Her writing is beautiful, at times lyrical, giving the narrative the majesty of an epic. Hardships, threats, and glimmers of opportunity and justice mark these histories of everyday, recognizable Americans. The north and west were not promised lands. Racism, in familiar and new forms, were corrosive. Alexander brings this and more to life. She celebrates the courage of African Americans who took tremendous risks to build decent lives for themselves and their families. It is history, but not distant history.

Alexander, an attorney, Supreme Court law clerk, and now a professor, argues that the US criminal justice system, under the aegis of the “war on drugs” and mass incarceration, has created a racial caste system. She acknowledges that hers is a radically re-seeing of recent history. She notes that “only after years of working on criminal justice reform did my own focus finally shift.” Once Alexander started down the path of clarifying her thesis, she saw multiple pieces coming together as an institutional response to the threat of civil rights.

Her book rests on social science, public policy, law, politics, and history. She explains that the war on drugs, fueled by a media storm over crack, established ever greater mechanisms for incarcerating drug users and those involved in the drug trade. The laws and their policing, however, have been applied disproportionately to people of color. Studies show that white Americans use drugs at a slightly higher rate that African Americans or Hispanics. African Americans – especially males – are much more likely to be questioned, arrested, and tied up in the criminal justice system than whites. This is not necessarily because of the racism of individual police or prosecutors. Alexander argues that the system has recast black males as criminals. Once society defines someone as a criminal, all manner of punishments – formal an informal are permitted if not encouraged. Criminals do not vote, do not have access to many services, and are rarely candidates for employment and advancement. Once defined as criminal, people are trapped and there is no migration or place to go.

The numbers are staggering. Alexander stresses that continuing trends will lead to nearly one of three African American males being imprisoned. The United States has the largest prison population in the world. Nearly 3% of all Americans are under some form of correctional supervision. Alexander is careful to distinguish between crimes of violence and drug related crimes. She sees need for policing and prisons. However, she does not believe tinkering will help. She calls for a radical restructuring and abandoning the war on drugs.

Parallels between Alexander’s and Wilkerson’s subjects are unmistakable. They make clear that broad societal, political, and cultural trends and practice, regardless of the values and thinking of individuals, can have effects that are best understood through a racial lens. They call for racial awareness. Yes, there has been progress, but that does not mean that we should be indifferent to race.

The discussion around race is shifting. Scholars such as Wilkerson and Alexander provoke us to move beyond discussions of diversity and identity, arguing that we need to look at outcomes and consequences to grasp the prevalence of race in American society. This is a challenge for higher education – and a tremendous opportunity, too.

David Potash